From Donbas to Russo-Ukrainian War

Anna Greszta

Subproject 3 addresses cultural engagements with the Russian war in Ukraine. The 2010s have seen a series of escalating confrontations between Russia and Ukraine. In 2013, protests (further called: “Euromaidan”) broke out in Kyiv in response to the excessive concentration of power in the hands of President Viktor Yanukovych and his sudden decision to break with the course of European integration, instead choosing closer ties to Russia. Euromaidan demonstrations were followed by violent clashes between protesters and security forces, Yanukovych’s decampment to Russia and the snap presidential elections. The civic unease in the Eastern parts of Ukraine, Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea, and the subsequent creation of self-proclaimed ‘people’s republics’ in parts of Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts (collectively called Donbas) by Russia-backed separatists marked the beginning of the protracted war.

So far, an academic consensus regarding terminology used to describe military interventions in Donbas has not been reached, with the framing varying from ‘civil war’ (e.g., Matsuzako 2017), a term highlighting the domestic dynamics of the conflict, to “Russia-Ukraine war” (e.g., Kuzio 2018). Nonetheless, the full-scale Russian aggression that broke out in the end of February 2022 calls for critical reconsideration of the academic language used to analyze this war. As such, in this project, while acknowledging differences of the before- and after- February 2022, the term ‘Russo-Ukrainian War’ or “Russian war in Ukraine” will be used to cover events from 2014 up till the present.

The Russo-Ukrainian war is as much a military conflict as it is an information war, and its most explosive manifestations pivot on imaginations of memory and conspiracy. Propagandistic Russian media outlets painted the Euromaidan protests as a ‘USA-led uprising’ and an illegitimate installation of a ‘fascist’ or ‘neo-Nazi regime.’ Against this backdrop, prevalent stories and images in Russian media and culture have mobilized World War II narratives to present the current war as a ‘special military operation to de-nazify Ukraine,’ a heroic Russian battle against the dangers of Ukrainian “fascism,” while other Russian imaginations revive late-Soviet stories about the insidious infringements of devious American imperialists, who are, supposedly, still or again keen to destabilize Russia through carefully orchestrated conflicts on its borders (Yablokov 2018: 162-184).

In the Donbas-limited phase of the conflict the term “Anti-Terrorist Operation” (ATO) was used by the government of Ukraine and the state media to name the Ukrainian military intervention in the region. As such, the frame of terrorism promoted by then-president Poroshenko was aimed at creating discursive alliances and analogies with acts of terror in the West. Other Ukrainian interpretations of the conflict frequently draw historical parallels with earlier instances of cultural or political encroachment from Moscow (Marples 2015: 11) or present the (information) war as the latest episode in a longstanding Soviet/Russian tradition of disinformation, hush-ups and propaganda.

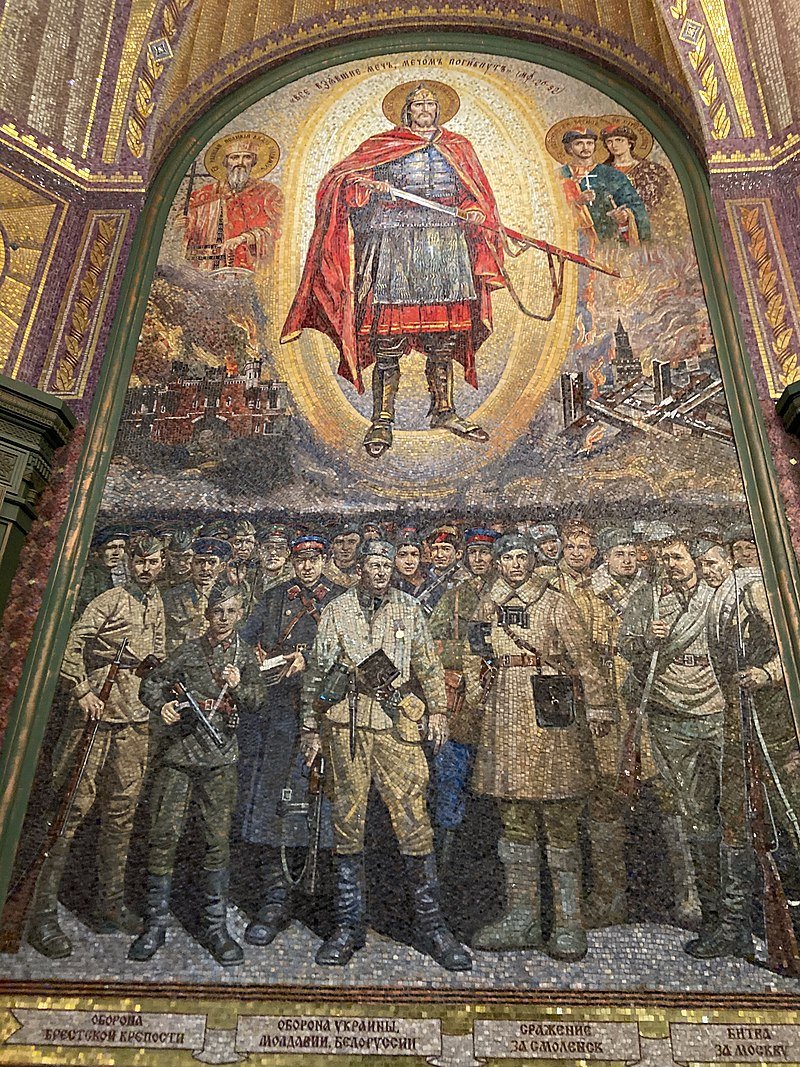

The Russo-Ukrainian war is often portrayed as the prime example of a nonlinear, ambiguous “hybrid war” with an extensive use of non-military means of manipulation and deceit (Pomerantsev and Weiss 2014). One of the points of departure in this project is the exploration of post-truth sensibilities and conspiratorial logic in the interpretation and representations of this war. I will use a set of “objects of war” – varying from Serhii Zhadan’s novel ”The Orphenage”, through a comedy television series ”Servant of the People” starring Volodymyr Zelensky, to Putin’s Cathedral of the Russian Armed Forces. Inspired by and immersed in the cultural analysis and anthropological traditions, the project will examine the intersections of memory and conspiracy cultures in the landscape of objects representing Russian war in Ukraine.

Image: A mosaic in the Main Cathedral of the Russian Armed Forces. Great Patriotic War mythology and Eastern Orthodox iconography intertwined. Picture by Natalia Senatorova CC-BY-4.0

Works Cited

Kuzio, Taras. “Euromaidan Revolution, Crimea and Russia–Ukraine War: Why It is Time for a Review of Ukrainian–Russian Studies.” Eurasian Geography and Economics, vol. 59, no. 3-4, 2018, pp. 529-53.

Marples, David. “Ethnic and Social Composition of Ukraine’s Regions and Voting Patterns.” Ukraine and Russia: People, Politics, Propaganda and Perspectives, edited by Agnieszka Pikulicka-Wilczewska and Richard Sakwa, E-International Relations Publishing, 2015, pp. 9-18.

Matsuzato, Kimitaka. “The Donbass War: Outbreak and Deadlock. Demokratizatsiya.” The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization, vol. 25, no. 2, 2017, pp. 175-201.

Pomerantsev, Peter and M. Weiss. The Menace of Unreality: How the Kremlin Weaponizes Information, Culture, and Money. Institute of Modern Russia, 2014.

Yablokov, Ilya. Fortress Russia: Conspiracy Theories in the Post-Soviet World. Polity Press, 2018.